Christine Kenyon Jones discusses one of the newly-published portraits of Byron in Dangerous to Show: Byron and His Portraits by Geoffrey Bond and Christine Kenyon Jones (Unicorn Press, £25 and special offer for Byron Society members).

In his early days of fame, around 1813-15, Byron was super-pernickety about his portraits and hoped to be able to control the way he was portrayed by artists such as Thomas Phillips. ‘No ‘pens and books on the canvas’, he decreed, while going so far as to destroy the plate of one of the engravings of this picture which he disliked.

By 1821 he had become more resigned to his inability to regulate the way he was visually portrayed, and he was flattered by a request to sculpt him from the distinguished Florentine sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini, who had been a favourite of Napoleon. And so, despite his resolve to ‘sit no more for such vanities’, Byron agreed to pose for Bartolini on condition that Teresa Guiccioli’s bust was taken as well as his own.

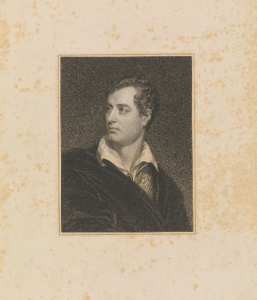

The project started well. Thomas Medwin spent ‘day after day’ at the Casa Lanfranchi in Pisa watching Byron sitting to Bartolini, and he described the resulting clay model as ‘an admirable likeness’. What seems to be this bust has in fact just recently come into the public domain, when it was put up for auction in 2019, and is in excellent condition – all the more remarkable because it is made of unfired clay.

Here we see Byron with his head slightly turned, as if in conversation. The portrayal is animated and naturalistic, and Byron must have been reasonably content with it in this form.

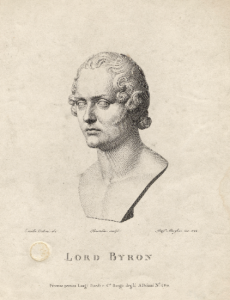

It then went off to Bartolini’s studio to be used as a model for the marble versions of the bust: one of which with classically-draped shoulders is now in South Africa, while another with a bare neck and shoulders can be found in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

The NPG copy, although signed by Bartolini, already seems less lively: the angle of the head is lower and the hair seems to overwhelm the face (Teresa had tried unsuccessfully to get Byron to tuck it behind his ears while posing). Byron in fact never saw this version of the bust, or the South African one, and the next and only representation of it he did see was an engraving by Raphael Morghen (also a favourite artist of Napoleon’s) – which horrified him.

‘It may be like for aught I know as it exactly resembles a superannuated Jesuit’, he wrote ruefully to John Murray. And worse: ‘my mind misgives me that it is hideously like. If it is – I cannot be long for this world – for it overlooks seventy’. This was, alas, prophetic, because although Byron never made it to 70 within two years of writing this he was dead at the age of 36 from fever in Missolonghi.