Welcome to the Byron Society

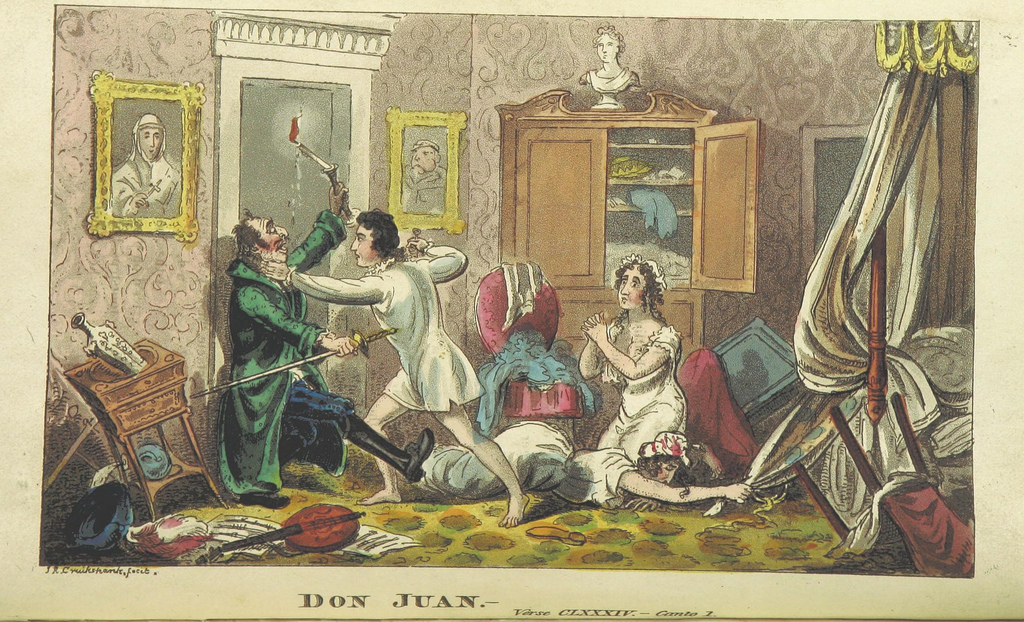

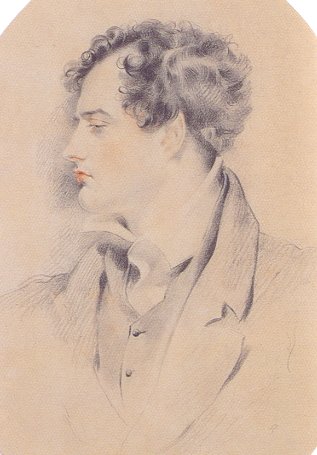

The Byron Society celebrates the life and works of Lord George Gordon Byron (1788-1824), a poet, traveller and revolutionary.

Based in London, but hosting events around the UK and abroad, the Byron Society brings together all those interested in the famous Romantic poet Lord Byron, whose controversial works and astonishing life have entranced readers for more than 200 years.

Established in the nineteenth century the Society was re-founded in London in 1971 to promote a wider and deeper knowledge of Byron’s life, works and circle. We offer you the chance to discover more about Byron, and to share your interest through talks, lectures, poetry readings, book launches, dinners, trips and other events.

We are a non-profit organisation and a registered charity (Charity No: 1197293).

JOIN THE BYRON SOCIETY TODAY

If you are interested in Lord Byron’s poetry and letters, his life and times, his relevance to today and the Romantic Movement in general, then our Society is the one for you.

✓ Talks, lectures, concerts, book launches, poetry readings.

✓ The opportunity to attend or participate in conferences.

✓ Two copies a year of the Byron Journal.

Annual Subscription

£30

GLOBAL BICENTENARY CELEBRATIONS AND EVENTS

We are tracking all activities relating to the 2024 bicentenary events celebrating Byron’s life and works, and commemorating his death 200 years ago on 19th April 1824, taking place across the world.

Collaborate with fellow architects. Showcase your projects.

2024 newstead abbey byron conference

26-27 April 2024, Newstead Abbey (Nottinghamshire)

This year’s conference is titled Provocative and Provoking: Fifty Shades of Byron, and the event will encourage papers exploring every aspect of Byron’s life, his poems, and his contemporary and current reception across the globe.

PhD Bursary Award

The Byron Society invites applications for a PhD bursary of up to £5,000 per year. PhD on any aspect of the life, work and /or influence of the poet Lord Byron.

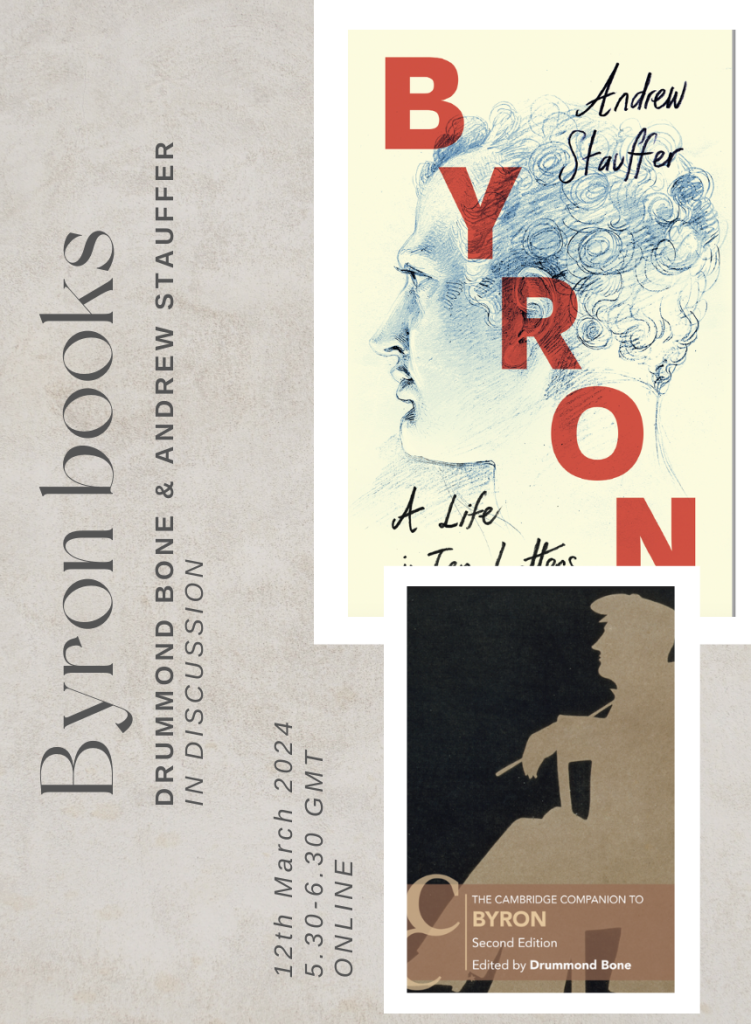

Upcoming Event

But words are things, and a small drop of ink

Falling like dew, upon a thought produces

That which makes thousands, perhaps millions, think.

– Lord Byron